Macroethics

Macroethics is looking at the big picture. Macroethics is working for the greater good of all rather than just your own needs and comforts. Macroethics is looking at the needs of society in the long term decades or centuries into the future, rather than what seems right for right now (hoping that when later comes, the people alive then will figure something out).

Some examples of macroethic thinking are not putting up fences around private property if doing so will block migratory animals. It’s giving talented youngsters access to higher education so they can contribute to society to the best of their ability. It’s setting up the tax laws so the best way for the moneyed classes to make even more money is by lifting up the economy for all rather than parasitizing off of it.

Macroethics is investing in sustainable development rather than using up a resource as quickly as possible, grabbing the profits, and running away. In the 1960’s-1970’s, a new major commuter mass transit system, BART, was built in the San Francisco Bay Area instead of yet another modern superhighway — which would have increased traffic, congestion, and pollution and would have been obsolete (at capacity) in just a few years. This is an example of designing a city so it can run efficiently, without using precious gasoline to do everything (and only really working for the well-to-do).

All of the above sounds like a good idea, but there is one macroethic issue that is getting ready to explode:

The biggest macroethic problem — population

This beleaguered planet of ours now has over 8 billion people (8 gigapops) on it — an unsustainable number. Resources are running short, and even when there are sufficient resources (like fossil fuels), just using them can cause secondary problems — like the release of carbon dioxide that causes global warming.

Who was Thomas Malthus?

Thomas Robert Malthus was an English cleric, scholar, and economist who lived from 1766 to 1834. He is best remembered for his slim volume, An Essay on the Principle of Population asserted that an increase in a nation’s food production improved the well-being of the people, but the improvement was only temporary because it led to population growth, which in turn restored the original per capita production level. In other words, humans had a propensity to utilize abundance for population growth rather than for maintaining a high standard of living. Eventually, people suffer hardship, beginning with the poor. He had 3 major theses:

◆ Food is necessary to human existence.

◆ Passion between man and woman is necessary and will continue nearly in its present state.

◆ The power of population is indefinitely greater than the earth’s power to produce subsistence for humans.

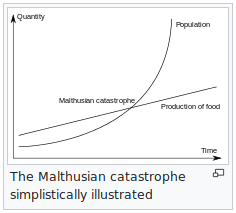

He postulates that the food supply increases arithmetically (along a straight line on a graph) while population increases geometrically (at an accelerating pace). Eventually, the demand for food outstrips the supply.

There’s no doubt that activities related to babymaking feel good. Nature (substitute God, evolution, or intelligent design if you wish) has given us highly efficient reproductive systems and the will to use them — which is good because that’s our guarantee human life will never end. But what nature hasn’t done is installed a stop switch for use when resources such as food run short.

And population growth has advantages. Public pension schemes are funded by working-age people; if there are fewer births today, there will be fewer taxpaying workers 30 years from now, and a proportionally larger retirement age group to support on diminishing tax revenues. And if you believe in reincarnation, there has to be an unclaimed body for you in the next lifetime; an increasing population ensures that a body will be there when you need it.

So what can we do about that?

Is disaster inevitable? Not if we implement Malthus’ “preventative checks” for keeping things in balance to forestall population growth — and as a bonus, put an end to poverty. He recommended “birth control” in the form of late marriage and total abstinence until then. (Note — this was before modern contraception. Malthus himself had 3 children.)

The macroethic burden

People aren’t going to take kindly to being told to limit their family sizes. No doubt about it, limiting your family to 1 or 2 children can be an unwelcome burden; a sacrifice that can be cancelled out by someone who “wants to have 4 or 5 children and don’t anybody dare tell me not to”. But if there is to be a macroethic burden, it should be shared fairly.

One of Malthus’ “remedies” was to reduce aid to the poor — grinding down their lifestyle until they are forced to not have children. I think this attitude is horrendous; it “solves” the problem by concentrating all of the ill effects on a small segment of the population, starving them into submission.

Basically, it comes down to three alternatives: use the preventive checks to avoid the problem, continue to advance technology so that need never catches up to it, or put our heads in the sand until one or more of the positive checks (see below) raises it’s ugly head.

And if the preventative checks fail?

The next step is that the environment will impose “positive checks” that cannot be avoided — specifically, hunger, disease, and war. Hunger is a result of insufficient food production, which is a result of environmental forces, while war is a result of nations fighting over what little is available. This cannot be stopped; except of course, by the timely application of the preventative checks.

Malthus and the connection to the Book of Revelation

Most people — myself included — have found the Bible Book of Revelation to be utterly confusing. In particular, I was mystified by the passage, “a day’s wage for a quart of flour, a day’s wage for three quarts of barley-meal, but do not damage the olive and the vine”. But what that really means is, on the 3rd horse is a food merchant representing famine, selling foodstuffs at unaffordable prices (note the scales he’s carrying). Together, these horsemen represent Conquest, War, Famine, and Death — not that much different from Malthus’ hunger, disease, and war. Perhaps this prediction on the end of society as we know it is not “a judgement of God” but rather the way a civilization like ours must end if it continues on its merry way.

Malthus was hated

Many people hated Malthus for his negative attitude towards life — and the limitations he advocated on family size. Many people resent the idea that their fertility should be restricted — “we are on earth to reproduce” they say. Why shouldn’t my spouse and I have 3 or 4 or even more if we can afford them? But if these children enter an overcrowded world, will there be a place for them when they grow up?

I like to compare Malthus to the weatherman who predicts a killer storm on the way — floods, hurricane winds, perhaps dangerous lightning — and then the storm hits and people die. Do you blame the weatherman for the storm? Of course not; if anything, he has saved lives by giving those who listened a chance to prepare for the worst.

But is Malthusianism still relevant in today’s world?

It’s easy to look around and say Malthus’ predictions have not come true. In particular, he completely missed the impact of the industrial revolution. And do you see any widespread starvation? But to not see the hunger in today’s world requires a bit of myopia, because even though we have lots to eat in the West, there is plenty of hunger and malnutrition in Asia and Africa. (And even in food-rich areas, problems with distribution have left pockets of poverty amid populations of plenty.)

Also, the food supply does not increase steadily; discoveries such as new and improved fertilizers boost farm output in leaps and bounds. Improved technology is good, but it comes when it comes — you can’t rely on it showing up when you need it the most. Potassium in particular is a powerful fertilizer; although a future shortage could trigger a crisis. And of course it’s not just food that people need.

China’s one-child policy

In 1980, China, straining under the weight of over a billion (thousand million) inhabitants (1 gigapop) inaugurated a “one child per family” policy. This slowly started to reduce the population growth rate to the point where it became easier to supply nearly everyone with food, clothing, and shelter.

But there were problems. What if that one child died? Traditionally, China has been a society where children take care of their aging parents. Families were China’s retirement/pension scheme. But if that one child died, that meant the parents were left with no one to care for them, either financially or with “hands on” care. And if that one child survived, there’s only so much he/she can do for them — four children can do more, collectively, than just one. (I did some calculations and discovered that if the one child policy were continued, the population of China would disappear entirely after 112 generations.) 🙂

Some exceptions to one child

Families that had a second child were required to pay a fine. And those who wouldn’t, or couldn’t, were not allowed to register the birth — resulting in a small army of “nonpersons”.

But there were exceptions — if twins or triplets were born, that counted the same as one birth (this created a loophole where mothers could take fertility drugs to have multiple births). If either of the parents were an only child, then that couple could have two. Starting in the mid-’80’s, rural families were allowed to have a second child if the first was a daughter, to alleviate the shortage of farm workers.

Problems with the policy

The biggest problem with “one child” was China became an aging society, with people moving up to middle- and old-age faster than young children were being born — resulting in a growing shortage of working-age people to do the jobs and pay taxes.

So China started modifying it’s policy to allow a couple where at least one of them was an only child, to have a second child. And then to allow all rural families to have a second child. Finally, in 2016, all Chinese families were allowed to have two children (increased to three in 2021).

But did it work?

In spite of all of the above, China’s population kept on growing, to 1.4 gigapops today. But experts have predicted that sometime this decade, that trend will reverse, and the count there will begin to shrink. This would be the first population decrease there since the great famine of 1959 – 1961.

At the very least, the one-child policy has slowed the growth of the people there to less than what it would have been otherwise. And perhaps avoiding another great famine, which is the whole point.

India and other poor countries

In some of the very poor countries, it is seen as common sense to have more children than you wanted — conditions were so difficult there, you knew some of them would die, so you needed extras.

The Population Bomb

In 1968 Paul and Anne Erlich wrote the book, The Population Bomb predicting worldwide famine and other upheavals due to population growth. It has largely been discredited because “the bomb hasn’t gone off yet”, but in my opinion, that fuse is still burning.

How the animals do it

It’s common in the life sciences to look at how wild animals approach a situation and then compare them to what humans do. How do animals approach macroethics? They simply have as much sex as they want, and when the females are in heat, that’s a lot. They have big broods, although in the long term only about 2 of each breeding couple survive. (Actually an animal population waxes and wanes according to the varying food supply [which in turn varies with the amount that the animals have eaten up]. The computer simulation grain, mice, and eagles shows an example of this.)

In some animals, such as pigs, the momma pig sometimes has more piglets than teats with which to feed them. This results in a competition which often results in tragedy for the those who can’t fight their way in.

I think we humans deserve better than that. So let’s forget about how the animals do it and instead concentrate on building a better world.

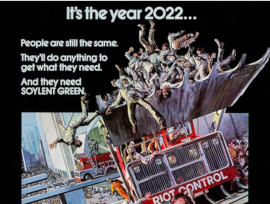

Lessons from the ’70’s

In 1972, the movie Soylent Green was filmed about an overpopulated world 50 years into the future. On the sidewalks everywhere were bunches of people hanging around with nowhere to go and nothing to do, hoping for the next government handout to come soon, to give them enough to eat to see them through to another day. And when was this dystopian world supposed to come about? Let’s see, 1972 plus 50 years — oh my gosh, that would be this year, 2022! The description of the movie begins “With the world ravaged by the greenhouse effect and overpopulation”. Now that we have global warming and a world filled with 8 gigapops, I’d say they got that part of the prediction right. Although our world isn’t nearly as bad as the world of Soylent Green, we’re seeing the beginnings of population pressure today.

In the movie, it is always hot out, usually over 90°F / 30°C. “Real food” is very expensive, like $150 for a small jar of strawberry jam. If you can’t afford that, there’s always “manufactured” food made from lentils, plankton, and soybeans — and even that is in short supply!

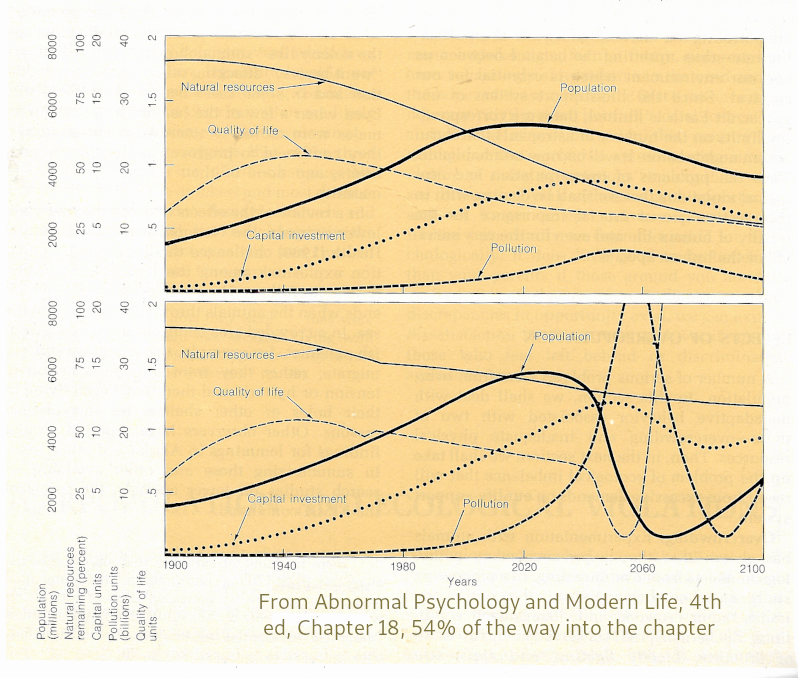

At the bottom of a big cardboard box I found a copy of Abnormal Psychology and Modern Life, 4th edition, published in 1971. In the chapter on Maladaptive Behavior of Groups, there were two graphs warning about mass death in the future — one from lack of resources, and the other warning about pollution (and greenhouse gases causing global warming certainly counts as pollution). The pollution graph in particular shows a fast decrease in population as the world becomes unlivable.

The dark side of macroethics

There is an alternative to reducing population growth. That is to prepare for the inevitable war that will result when the food runs short, and fight for whatever you can steal from your neighbors. This strategy requires encouraging rather than discouraging population growth, particularly males of military age, so as to be able to field a strong army when the time comes. (In this context, I like to say that someone who wants it all for himself and nothing for the other guy “is being macroethic”.)

Germany’s Merkel and the AfD

In and around 2015, Germany’s Angela Merkel allowed unrestricted immigration of war refugees into Germany — ostensibly to increase the number of “young workers” to support the aging retirees there. I disagree with this sort of thing, because looking at the long term (which is what macroethics is all about) eventually those immigrants will retire, which will require even more young workers to take care of them. This, to me, is not social policy — it’s a Ponzi scheme.

The Alternative for Deutschland (Germany) party opposed this move, saying that foreign refugees should not be welcome. Which sounded workable to me, until I found out what the AfD wanted to do instead — to increase the already generous subsidies given to German parents, to encourage even more births (at the expense of taxpayers, including taxpayers without children). In other words, they want to reduce population growth with one hand while increasing it with the other. This undermines any attempt to reduce the macroethic pressure on today’s Germany. (And have you seen the price of real estate there lately?)

Two sides to this issue

This issue is a complex one, with good arguments on both sides. Let me close with an imaginary debate between two people very passionate on the subject — Mr. Green and Mr. Blue:

Hey, I heard your wife has another bun in the oven. Congratulations!

Yes, we’re very proud.

How many does that make now? Four?

Yes. And speaking of this, when are you going to do your part?

Not this again.

Yes, this. Don’t tell me you’re in favor of the human race going extinct?

With over 8 billion people in the world, I don’t think that’s a problem.

But population decrease means fewer working-age people to support retirees. We’re both getting older, don’t you want to be supported in your old age?

An increasing population means everything gets more expensive, from food to housing to everything else. If we don’t increase the population, that means a lower cost of living, making life easier for everyone. And what happens when there’s not enough food for everyone at any price?

That’s a problem that’s not going to happen. Modern fertilizers have made the desert bloom!

Until there’s not enough water, which is happening in many farming districts.

We’ll figure something out. We always have.

Like start a war, maybe? When resources run short, that has always been the answer.

War is not inevitable. But if it comes to that, our country is ready!

With fewer people, we won’t need a war.

No problem then. Go and visit every country on Earth, and convince them to limit their population. But you know some won’t do it. And if that means war is inevitable, then we’ll do what we have to do.

But….

And there’s a good argument for population growth right there. If it does come down to a shooting war, you need a big, strong army. By having lots of kids now, that guarantees our access to resources later.

That’s the same argument Hitler used.

By not doing your reproductive duty, you’re just being selfish.

No, I think you’re being selfish. You want to build up your family, your house, your clan, and have people like me help pay for it with taxpayer-funded projects.

Look, you should just try it. I guarantee it will make you happy.

And if it doesn’t? Will you take the child from me and raise it yourself?

No, of course not.