I was thumbing through my old copy of Mr. Scott’s Guide To The Enterprise when I realized there was no mention of the thing that makes warp drive possible, the warp nacelle. No internal diagram, no explanation of the mechanics, not even a picture. So if they won’t tell me how warp propulsion works, I’ll just make up an explanation of my own.

Now what would we put in such an explanation? We’d have to put in a little bit of everything we could imagine. So let’s put in some uranium from the Lensman series, Tesla-style high voltages, gravity warping per T. T. Brown, and dilithium. Oh we just have to have some dilithium.

The capacitor

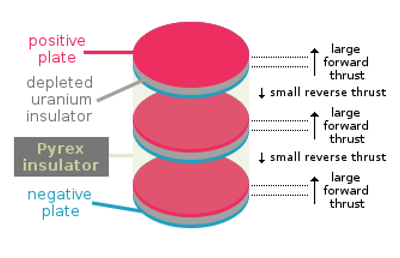

Let’s start with one of the lowliest pieces of electronic equipment there is, the capacitor. A capacitor at its simplest is two sheets of metal separated by an insulator. One piece of metal is charged positively while the other is charged negatively. Your normal capacitor like you would find in a stereo or personal computer has these metal sheets curled around each other to save space. But for our purposes we’ll use two flat, round metal plates about 40 ft/12 m in diameter. Put a thin insulating layer in between, charge it up to at least 40,000 volts, and it will move in the direction of the positive plate.

Since we’re changing the laws of physics, in spite of what Mr. Scott always said we can’t do, we’ll have this motion be entirely reactionless — no equal reaction in the opposite direction.

Since we’re changing the laws of physics, in spite of what Mr. Scott always said we can’t do, we’ll have this motion be entirely reactionless — no equal reaction in the opposite direction.

The ability of a capacitor to store electricity is inversely proportional to the distance between the plates. But the thinner the insulator, the more likely it is to short out — and have the electricity flash across in the form of a big spark (or a small lightningbolt). So let’s make the insulator out of an exotic material, such as depleted uranium. Now we can charge it up more, to the realm of 1,000,000 volts.

Place two of these, one in front of the other, and they will provide almost twice the force. Why almost? Because the two middle plates will generate a thrust in the opposite direction. To minimize this, put some space between the two. As the separation increases, the force decreases rapidly, so the little bit of reverse thrust generated can be ignored. The larger distance between the plates means a cheaper insulator, like Pyrex, can be substituted.

Place two of these, one in front of the other, and they will provide almost twice the force. Why almost? Because the two middle plates will generate a thrust in the opposite direction. To minimize this, put some space between the two. As the separation increases, the force decreases rapidly, so the little bit of reverse thrust generated can be ignored. The larger distance between the plates means a cheaper insulator, like Pyrex, can be substituted.

Beyond warp 4

Another problem comes in when the plates become “tired” from being charged up continuously, making it difficult to sustain speeds above warp 4 (old scale). To counteract this we can mix in a little AC with the DC used to make the whole thing go. To handle the high voltage, use a power mixer made with dilithium.

A big column of propulsive capacitors — times two — can give us enough oomph to take us to the stars. See you on Pollux II !